Book Review

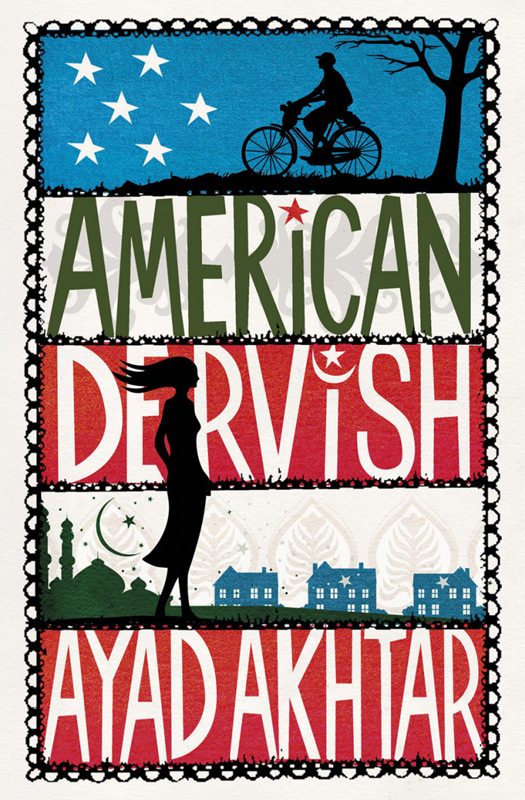

American Dervish by Ayad Akhtar

You’ve read this tale, or something like it, before: young protagonist is emotionally and/or sexually awakened by the entrance into their lives of a new person: an iconoclast or unconventional character, who throws their current perspectives into disarray. You know that the offending new character will somehow spark a series of events that lead to moral or physical destruction, or perhaps both. You’ve read it before, but you keep reading, perhaps because you’re also being awakened like the protagonist. Such is not the case with the debut novel from first-generation Pakistani-American Ayad Akhtar. Akhtar’s novel doesn’t so much awaken the reader as it displaces and confounds them, quite deliberately, by introducing a world where the peri-puberty internal upheavals that most of us experienced – awkward sexual encounters, changing bodies, social prejudices drawn on economic, ethnic or gendered lines – seem damningly mundane when compared to the protagonist’s. American Dervish charts territory we need to explore that is unfamiliar to most Australians; of what it is like growing up as a first-generation Muslim in a Westernised Christian culture, and also of the tensions existing between Muslims and other non-Christian religions, and within the Islamic community itself. Writing the novel, Akhtar aspired to ‘give people a sense of what it was like to grow up Muslim in America’. It would take a fellow Muslim-American to claim his success or failure, but he certainly gives a deep insight into what growing up with cultural clash is like for his protagonist and maybe what is was like for himself.

The story charts the coming-of-age catharsis of first-generation Pakistani-American Hayat Shah, whose vacillations regarding his own faith are focussed towards fanatacism by the arrival of his mother’s best friend, Mina, into the Shah household. Mina is beautiful, intelligent, well-read, and a devout Muslim. She and her son have escaped her abusive husband in Pakistan, whose use of violence against her is justified by the same text she encourages the young Hayat to find solace in. Mina enters the Shah household as a foil to Hayat’s religiously apathetic parents – his neurologist father is far too taken with the taboos of alcohol and adultery to bother much with the Koran, and his long-suffering mother leans on Islam as a social anchor but not a moral crutch. Mina begins to read the Koran with Hayat, encouraging him to become an Islamic scholar (a hafiz, who has memorised the entire Koran). Mina’s moral guidance and physical beauty forge dangerous mettle in the adolescent Hayat’s mind and it’s not surprising that he takes it particularly poorly when she begins dating Nathan Wolfsohn,, a Jewish doctor and Hayat’s father’s colleague. The tryst between Mina and Nathan pushes Hayat’s religious leanings towards the extreme, inciting him to read – and act on - passages from the Koran that are damning to the Jewish faithful, essentially propelling the story towards the entropic ending one senses from the start. Indeed, the problematic relationship between the two religions forms a nut around which the story winds and is explored in several ways throughout the novel: Hayat has a childhood best friend who is Jewish, a Jewish orthopod fixes his broken arm at a time when Hayat’s religious fervor is building, Hayat is witness to a confrontational after-dinner discussion on Judaism between his father and the Muslim men Dr. Shah denigrates. To confuse things, Hayat’s mother has an atypical appreciation for the Jewish faith, gleaned from her own father, that sees her telling Hayat that Jews “are the special people, blessed by God above others, difficult to bear at times, perhaps –like spoilt children in general – but with much to teach us all.” Surely this situation in its entirety can’t be typical of what it is like to grow up Muslim in America, but these vignettes do cast light on aspects of the first-generation experience and the competing interests affecting children growing up cross-culturally, who are forbidden assimilation by the prejudices of their parents’ homelands.

Akhbar tells the story from the perspective of Hayat in the aftermath, a college student now redeemed from his childhood faith and recounting the story of Mina to his new Jewish girlfriend. Plot aside, the novel is an easy read; that is to say, the prose used is simple, thought a bit heavy handed at times: lines like “Mina first noticed the selection of magazines showing American beauties with impossibly wide smiles, their hairstyles gorgeously tousled by the breeze of freedom that seemed to blow across every glossy cover” come a bit too often – though perhaps with the desired effect of drenching the reader in the sensory onslaught that adolescence brings, let alone growing up amongst spice-filled kitchens and dogma-suffused conflicting worlds. Our protagonist is painfully sensitive in his youth, and tends to observe more than his lived experience can comprehend. Perhaps because of this, it’s a shame that the complexities of Hayat’s inner machinations and those of his closest family are so adeptly detailed, but those of the orbiting characters – the Muslim Imam and his supporting community, the wives of the men in the after-dinner discussion – are reduced to caricatures that serve more to support a Fox Media idea of Islam than to broaden the reader’s knowledge of the religion. One can’t be sure how much of the tale is autobiographical and how much is fiction, but this tendency to slate some aspects of Muslim culture – indeed, of fundamentalism in any form – suggest that Akhtar wasn’t thrilled about some aspects of growing up first-generation Pakistani-American. Hayat’s story is relatively unique in fiction, but the frustration of battling one’s own moral compass against one imposed upon them is common to many first-generation children of immigrant parents. Overall, the story seems an important one to tell, particularly at this geopolitical juncture. It throws into light the complexities and sublime / ridiculous fulcrum that so many important events teeter on – the gravity of so many belief-based decisions neutered by the notion that, in the case of American Dervish, our protagonist’s devotion is born of a secular infatuation with his aunt. Akhtar’s exploration of the Koran is educational, if not representative, of a religion that we need to learn more about. The novel is enjoyable, but also exhausting, confronting, and complex – like so many important things are.

By Siobhan Thakur